I found this article on The Criterion Collection website and thought it would be great to share on what would have been Russ Meyer’s 100th birthday. You can find the original here but I’ve typed it out below as well. Happy 100th Birthday Russ!

The following account of a visit to the Beyond the Valley of the Dolls set is excerpted from a piece that originally appeared in the January 7, 1970, issue of the University of California, Los Angeles, newspaper, the Daily Bruin, under the headline “18—Count ’Em—18 Couplings and an R Rating: Russ Meyer in Hollywood.” Its author, who went on to become a television writer as well as a friend of Meyer’s, was a UCLA student at the time.

Countless boring and laughable sexploitation films prove that it takes more than naked women to make arousing nude scenes. Surprisingly, many of Hollywood’s best directors have been unable to make use of their talents when dealing with nude scenes—probably because of lack of experience in that field. Realizing this, Richard Zanuck, president of Twentieth Century-Fox, started looking in some unlikely places to find a man to direct a sequel to Valley of the Dolls. In his travels, Zanuck evidently took in quite a few films which did not meet the traditional Hollywood standards of “good” movies. One of the films was Vixen!, a dazzling assortment of adultery, incest, lesbianism, racism, violence, and even politics, all photographed well enough to rival any Hollywood production—a rare achievement for a sexploitation film.

Production values aside, the most impressive thing about Vixen! is a matter of simple economics. The film cost $70,000 to make and its estimated gross is in the neighborhood of $6 million. This arithmetic did not escape Zanuck, and so he invited Vixen!’s creator, Russ Meyer, to come to Twentieth to produce, direct, and help write Beyond the Valley of the Dolls.

Meyer’s progress in the studio system is of special interest because his background as a one-man show puts him in the same position as many of the talented young people who are graduating from film schools. Prevented by odd hiring practices from working for the studios, Meyer had to go into independent production. Constrained by lack of funds, he had to do his best with very little. In the process, he became adept in directing, editing, writing, and in most of the other skills that are required between the time a film is conceived and the time it appears on the screen.

For Meyer, the offer from Twentieth was the fulfillment of a long-standing ambition. As a fourteen-year-old in Oakland, he was given an 8 mm movie camera and projector by his mother as a Christmas present. Captured by the thrill of making his very own movies, Meyer started shooting what would have to be called documentaries. One of them, shot on Catalina, won an award from Kodak. In 1942, at the age of eighteen, Meyer joined the army and was trained as a combat photographer by Art Lloyd (who filmed the Our Gang comedies) and Joe Ruttenberg, another noted cinematographer. For all his subsequent achievements, Meyer still rates the time he spent shooting combat newsreels as the most memorable time of his life. “It was real action and excitement! Nothing could compare to it!” Meyer said with boyish enthusiasm.

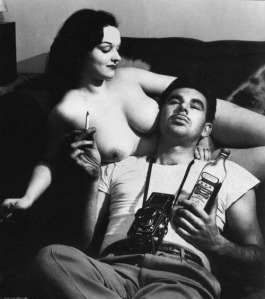

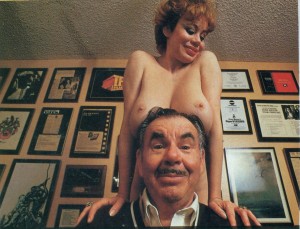

After his discharge, things didn’t go so well for Meyer. He came to Hollywood to work as a cinematographer, but he couldn’t get into the union, so he had to go to work making industrial films in San Francisco. (When he returned to Hollywood more than twenty years later, he had little difficulty entering the screen directors’ union. “You just pay them your two thousand dollars, and they’re glad to have you,” he said.) Spending his time making educational films for employees of supermarket chains, oil companies, and others, Meyer grew bored and took up magazine photography. His glamour photography appeared in Playboy and similar magazines, as he rose to the top of the field. But Meyer didn’t stay away from movies for long.

Meyer’s first girlie film was little more than a recording of a burlesque show. Called The French Peep Show, it was done for Pete DeCenzie, owner of Oakland’s El Rey burlesque theater. In 1959, DeCenzie decided to break from current trends in nudies and make one with a story. Meyer more or less took over the project, and the result was the most famous girlie film up to its time—The Immoral Mr. Teas. In it, one of Meyer’s old Army friends played a delivery boy who sees all the women he encounters as naked. For the film’s finale, there is a fifteen-minute sequence in which Teas sees the three principal girls sunbathe, swim, and hike through the woods—in the nude, of course.

Mr. Teas was filmed in four days, and it cost $24,000 to make. Its gross of $1 million enabled Meyer to make more films, refining his techniques and developing his skills all the while. In films like Eve and the Handyman (which starred his wife); Erotica; Wild Gals of the Naked West; The Naked Camera; Heavenly Bodies; Europe in the Raw!; Lorna; Mudhoney; Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!; Motorpsycho; Good Morning . . . and Goodbye!; and Finders Keepers, Lovers Weepers!, Meyer shows what amounts to an overriding concern for exteriors, which goes beyond the attractive (and inexpensive) natural scenery that graces most of his films and his perfectionistic photography. His concern for surfaces also affects his characters, for they rarely turn out to be more than they appear to be. A puffy delivery boy turns out to be a harmless voyeur, even in his own fantasies; the ubiquitous busty women are invariably oversexed; and an evil-looking dark-haired girl is capable of breaking a man’s back with her bare hands. “I don’t pretend to be some kind of sensitive artist,” Meyer sneered. “Give me a movie where a car crashes into a building and the driver gets stabbed by a bosomy blonde, who gets carried away by a dwarf musician. Films should run like express trains!”

Among the arts, movies would seem to be particularly hospitable to object-oriented people. Not that these people can compete with Bergman or Antonioni, but they have the potential to make exciting action films, broad comedies—and good nudies. Not too surprisingly, Meyer has indicated that he wants to work on action films (one possible project: The Final Steal, which may star Johnny Cash), and later, perhaps, comedies, “if I can ever find someone like Bill Fields.”

The as yet unreleased Cherry, Harry & Raquel!, which may be Meyer’s last low-budget sexploitation film, reflects its creator’s changing interests. To be sure, there is still the element of comedy, which has been present to one extent or another in most of Meyer’s work, from the wisecracking narration of Mr. Teas to the sexual parody of Vixen!. Cherry also boasts plenty of action—a couple of gunfights and an exciting car chase. The action, in fact, overshadows the sex when at the film’s end Meyer intercuts Cherry and Raquel’s gratuitous love scene with Harry’s tense gunfight. Despite the fact that the scene is a very revealing view of lesbian lovemaking, it comes off as a distraction to the important action of the shoot-out.

Cherry, of course, doesn’t lack the ingredient that has made Meyer famous. There’s enough nudity to satisfy the patrons of any “art house.” Unlike Meyer’s earliest films, Cherry depicts a number of sex acts. “Did you notice?” Meyer asked. “We had a very frank blow job at the beginning.” Nevertheless, the shift in emphasis from sex to the relatively new field of violence is revealing of Meyer’s basic orientation in objects and exteriors. “I’m tired of sex. I’ve shown every position and combination of partners, and there’s not much else to do, is there?” Of course there is. For one thing, relatively few films have contributed any sort of psychological insight to sexual matters. But Meyer’s interest is in what people do, not why they do it, and so he goes to Twentieth Century-Fox to film Beyond the Valley of the Dolls.

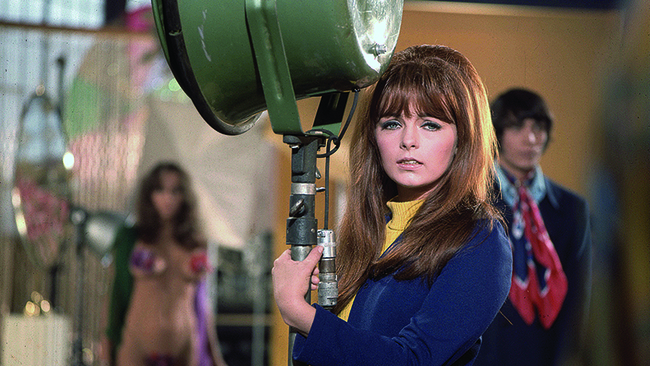

In early December, I wanted on to the Dolls set where the Westmont High senior prom was being filmed. The set was unimaginably sleazy and cheap, and the extras looked extremely uncomfortable. In other words, it looked just like a real high school dance. Onstage were two graduates from Playboy’s centerfold, Dolly Read (May 1966) and Cynthia Myers (December 1968). Along with dancer Marcia McBroom on drums, the girls comprised a rock trio which, through the course of the film, makes it big and then goes to pot—literally and figuratively. According to the script, the prom scene is preceded by a flash-forward which may never be filmed if Meyer wants an “R” rating, as he claims he does. In this earlier scene, we are treated to an extreme close-up in which a gun barrel traces its way up the middle of a sleeping girl’s naked body. The barrel is then inserted into the girl’s mouth and only after a few enormously suggestive seconds does she realize that what has been thrust into her mouth is cold steel and not something else. She screams, and her scream becomes that of Dolly Read singing at the prom.

The prom scene was filmed in a way that must have seemed strange to a man who in the past had to be so careful about budgetary restrictions. The one song that the girls perform was shot at least a dozen times, all from different angles. Later, during the editing, pieces of each shot will be incorporated into the sequence. “We’re getting a lot of coverage,” Meyer said, and he can well afford it, as his budget is somewhere between one and two million dollars. But what about the old ways that had served him so well in the past? Did he feel that the forty assistants required by studio production would prevent him from controlling every aspect of his film, as he was used to doing in the past? “I love it here. With all these people helping you, you’re not so tired at night. I’d never go back to the old way.” His previous experience had been quite an asset to him, though. The film has been progressing right along on schedule, and it has not exceeded its budget. Meyer’s work in low-budget films has also enabled him to juggle shooting schedules, so that if an actress brings the wrong costume, for instance, he can shoot a completely different scene without so much as a day’s warning.

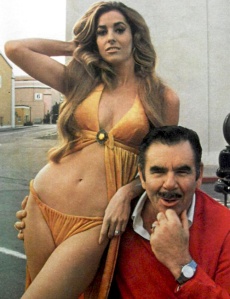

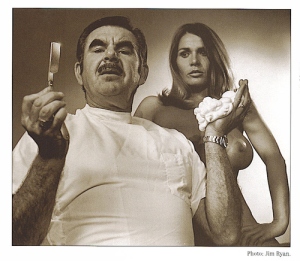

Meyer may like the studios, but there’s evidence that he may not fit in as well as he would like. Invariably dressed in Levi’s, a pullover sweater, and track shoes, Meyer is six feet tall and, at 240 pounds, is not a roly-poly fat man, but rather a wrestler or maybe an ex–football player—in other words, mean-looking. And the uncompromising toughness that is required by a one-man show is no asset in an industry where a bruised ego can mean a ruined career. Therefore, Meyer is making a special effort to be “diplomatic.” One afternoon, an actor kept forgetting his lines, through some fourteen takes. Not once did Meyer lose his temper, and instead, after every few takes, he offered the actor an opportunity to sit down and rest. Meyer’s patience was rewarded by take fifteen, a flawless glimpse of a dirty old high school principal. In addition, Meyer allots a generous share of his time to the press, even though he is resigned to being portrayed by them as a “casting-couch director.”

A few days later, Dolls was being filmed on the “French” street of the Twentieth Century lot. To save money, Meyer is shooting most of the film on the lot, and he is using sets that were originally built for other films. For this film, the French street was an alley behind a nightclub. As one of the girls in the rock trio leaves by taxi, a bisexual girl emerges from the back door and stares hungrily at the departing cab. “Who’s that girl in the doorway?” asked one of the technicians. “She’s the reason I’m here,” answered Meyer.

“That girl” was Erica Gavin, the star of Vixen!, the film which finally made the industry take notice of its director. Fortuitous as the film was for Meyer, its star has not even been able to use it as a credit when looking for acting assignments . . . which is hard to believe, because her portrayal of Vixen will long be remembered by anyone who has seen the film.

[ . . . ]

Who would believe that I had been on the set of a Russ Meyer movie and had not seen him film one of the scenes that had made him famous? I mentioned this to Meyer, and he replied that whenever one of the principal actresses is involved in a nude scene, outsiders and even some of the crew were barred from the set, “but this Wednesday we’re filming some stuff you might like.” Meyer’s estimation of my taste was accurate. Along with about forty members of the crew, a dozen actors and actresses, a few janitors, and assorted others, I watched Meyer direct a photo studio sequence which required a model to remove her bra for the critical appraisal of her female employer—and the admiring stares of the rest of us. It wasn’t much compared to Vixen!, but in keeping with Meyer’s policy of maximum coverage (or uncoverage), the sequence was shot about nine times.

Later that day, I saw the familiar face and even more familiar body of Haji, who has appeared in two of Meyer’s earlier films. She is one of the more than half dozen actors and actresses in Dolls who have worked for Meyer before. “They’ve done some-thing nice for me, so I thought I’d give them an opportunity to appear in a big film,” Meyer said. In addition to his own troupe of actors and actresses, Meyer used unknowns to fill out the cast of Dolls, because they don’t ask for as much money as “names,” and they’re less likely to become prima donnas. If the unknowns don’t have the acting experience of their more famous colleagues—well, as Meyer says, he relies heavily on action, quick cutting, and “express-train pacing,” which make sensitive performances unnecessary anyway.

After the day’s shooting, Meyer confirmed that his days as the foremost maker of exploitation films had left him relatively free of money worries. “I’ll tell you one thing, last year my company paid more than $400,000 in corporate taxes.” Why then does he continue making films? “I’d like to be recognized as a good filmmaker.” But could his desire for recognition drive him to make a film which might enhance his reputation but nevertheless be a financial failure? “No . . . absolutely not. There’s nothing more sad than a film that doesn’t do well at the box office. A couple of years ago, I made a film called Mudhoney. It got good reviews, but no one went to see it. Critiques aren’t worth shit.”

Meyer apparently wants to be recognized as a good filmmaker not by the critics but by the moviegoers, who show their appreciation in cold cash. Meyer is careful not to enter into any ventures which look like they might be unprofitable, but once he has selected a project, his only concern is the quality of the film. One of the reasons for this is that the profits, large as they often are, sometimes take years to come in. Money aside, though, if he were given a large sum of money and asked to do the film of his choice, what kind of a movie would he make? “Oh hell, I wouldn’t make one—I’d go fishing.”